October 21, 2021

My article on dyslexia got published by the Ark Valley Voice arkvalleyvoice.com/dismayed-by-dyslexia-look-for-the-hidden-strengths/ Dismayed by dyslexia? Look for the hidden strengths When my daughter was two years old, her closest friend was a boy I’ll call Mark. Mark had an odd habit: he looked at picture books upside down. He did not seem to know the difference. When Mark started school, he had a hard time learning how to read. While most of his peers were reading by first or second grade, he didn’t start to read until third grade. That didn’t mean he wasn’t intelligent. He excelled in other subjects, like math, and he had a remarkable spatial awareness. In fact, when he was 17, he disassembled an entire auto engine by himself, then—with the help of YouTube videos—put it back together perfectly. Mark has mild dyslexia, a learning disability that impairs his ability to read. Since October is National Dyslexia Awareness Month, I’m sharing Mark’s story for any parents or grandparents who are fretting over a child or grandchild who is not reading at their grade level. While dyslexia poses extra challenges for children, it also is often accompanied by special abilities. University of Michigan’s DyslexiaHelp website lists 10 areas of strength common to successful people with dyslexia—from the spatial reasoning I witnessed in Mark to thinking outside the box about business or social problems. In my career as a special education teacher, I’ve seen children with dyslexia come up with the most creative ideas and and excel in innovative, multi-dimensional thinking. They are great conversationalists and often have excellent people skills. But these kinds of characteristics are often overlooked as teachers and parents focus on a dyslexic child’s deficits. The child hears words like “slow” or “falling behind” and absorbs the shame that comes with these labels. Helping a child with dyslexia discover and practice what they’re good at is one of the best ways a parent, grandparent or other significant adult can build the extra confidence these children need. Also, make sure they get evaluated by their school, and then advocate for them. If they’re placed in a special program or given other assistance and they still don’t make progress, push harder; don’t simply accept that the school is doing all it can. Children with dyslexia need to be taught reading in a direct and structured way. They tend to respond well to a multi-sensory reading method that combines auditory, visual, and tactile strategies, and uses phonemic awareness. To help your struggling reader, here are some things to try at home: • Read to your child or provide her or him with audiobooks. This sparks an interest in reading and helps with comprehension, vocabulary, and other skills. This also lets them enjoy the books their peers are reading. • Use spell-checking and text-prediction software to help them express themselves in writing. Writing is an important form of self-expression, and kids with dyslexia deserve the same opportunities as other children to develop their creative thought processes. • consider working with a private reading instructor, like me. Contact me (707-601-1861) for a free reading assessment. |

Peak Reading

Sep 3, 2021

A third grader came to me recently unable to read AT ALL. Within two weeks, she was able to decode CCVC and CVCC (C=consonant; V=vowel) words and read short stories. What did it take to achieve this milestone? First, Phono-Graphix. This method works! Second, continuous instruction for four hours a week. Third, I engaged her creative mind by writing stories for her, and I enabled her to build confidence by using mostly words that she’d already learned how to decode. This gave her a feeling of success and reinforced her knowledge that words can be decoded. That may seem like an obvious technique, but in school the common practice is to give students texts with difficult words that they have no skills to decode. I also included photos of her and her dog (not shown). She enjoys reading stories that are about her and her dog. This also leads to fun little conversations giving her a much needed short break during a pretty intense hour of instruction. I find it enormously gratifying to be able to help a young learner like her on her way to becoming a reader. |

November 26, 2021

Over my years as a special ed teacher, I've often wondered what it would be like to have dyslexia—a learning disorder characterized by difficulty reading.

At a recent event organized by the Orton Academy in Colorado Springs, I experienced some of the challenges and difficulties facing people with dyslexia. While the sponsors didn't intend to simulate dyslexia precisely—which would be impossible—they designed a series of experiences to show us what a day at school for a kid with dyslexia might be like.

In one exercise, we had to trace a star while not looking at our paper but using only a mirror to guide our hand. This was extremely difficult. I felt like I had no control over my tracing hand. And as you might expect, I started to feel frustrated.

The role-playing "instructors" sought to encourage me and the other "students" by saying things like, “This is easy" and "You learned that in Kindergarten.” But these words actually made me feel worse because they were implying that I should be able to do what I found impossible. I even cursed, and I almost never curse.

Next, we had to listen and take notes on a recording of a teacher speaking to her class on a field trip. In addition to a very low volume level, the audio was made more distracting with other teachers' voices. So, to understand our teacher's instructions, we had to filter out the noise and identify and focus on her voice only.

I could not hear or understand much and wasn't able to put a single word on paper. Distracted and bored, I started doodling. And when I looked around and saw some of my fellow "students" had managed to write quite a bit, I started to compare myself negatively to them.

The teacher tried to encourage me and other slow note-takers by saying, “You can do it!” I unconsciously responded “No I can’t.” Now I was getting cheeky—and that's as unlike me as cursing, unless I'm in a stressful situation.

Next, the instructor exclaimed, “If you don’t finish, you stay in for recess.” She bent over me, and said harshly, “Stop doodling, get to work.”

That was a realistic response from a busy, stressed teacher. But even as an adult, just pretending to have dyslexia, I was hurt. I got the message: you're either not as smart or capable as the other students, or you're lazy.

As challenging as those exercises were, the short-story exercise was the most nerve wracking of all. We had to read a short story written with letters that were all reversed, like in a mirror. We received a one-minute instruction in how to decode these, and then the teacher started calling on us to read aloud.

Anxiety rippled through our little group of students. In my head, I prayed silently for the teacher to skip me. By the time it was my turn, I stumbled through the text. Others did better, and I felt bad about myself. Then the teacher asked us what the story was about. I had no clue. I was so focused on just reading the words, I paid no attention to the story.

So what did I learn in this frustrating three-hour process?

- Learning with dyslexia is different than learning without dyslexia. Unless teachers know how to modify their instruction for students with dyslexia, those students will feel frustrated, anxious and may develop a negative self-image.

-Students with dyslexia may need more time to finish an assignment.

-They may need multi-sensory teaching that involves movement, vision and hearing.

-They may need to work in an environment without distractions.

-They will probably feel anxious and intimidated when asked to read aloud to their classmates.

-Hearing things like, “this is easy” or even “you can do it,” may be taken as put-downs rather than encouragement.

-The worst tactic I experienced was the threat of losing recess. Kids need recess and should always get a chance to play, connect with their peers, and move their bodies. Threatening to take that bit of escape away from them does not give them the ability to work faster.

The Orton Academy will offer more of these simulations, and I encourage any teacher or parent to use this opportunity to gain greater empathy and understanding for what students with dyslexia go through.

Over my years as a special ed teacher, I've often wondered what it would be like to have dyslexia—a learning disorder characterized by difficulty reading.

At a recent event organized by the Orton Academy in Colorado Springs, I experienced some of the challenges and difficulties facing people with dyslexia. While the sponsors didn't intend to simulate dyslexia precisely—which would be impossible—they designed a series of experiences to show us what a day at school for a kid with dyslexia might be like.

In one exercise, we had to trace a star while not looking at our paper but using only a mirror to guide our hand. This was extremely difficult. I felt like I had no control over my tracing hand. And as you might expect, I started to feel frustrated.

The role-playing "instructors" sought to encourage me and the other "students" by saying things like, “This is easy" and "You learned that in Kindergarten.” But these words actually made me feel worse because they were implying that I should be able to do what I found impossible. I even cursed, and I almost never curse.

Next, we had to listen and take notes on a recording of a teacher speaking to her class on a field trip. In addition to a very low volume level, the audio was made more distracting with other teachers' voices. So, to understand our teacher's instructions, we had to filter out the noise and identify and focus on her voice only.

I could not hear or understand much and wasn't able to put a single word on paper. Distracted and bored, I started doodling. And when I looked around and saw some of my fellow "students" had managed to write quite a bit, I started to compare myself negatively to them.

The teacher tried to encourage me and other slow note-takers by saying, “You can do it!” I unconsciously responded “No I can’t.” Now I was getting cheeky—and that's as unlike me as cursing, unless I'm in a stressful situation.

Next, the instructor exclaimed, “If you don’t finish, you stay in for recess.” She bent over me, and said harshly, “Stop doodling, get to work.”

That was a realistic response from a busy, stressed teacher. But even as an adult, just pretending to have dyslexia, I was hurt. I got the message: you're either not as smart or capable as the other students, or you're lazy.

As challenging as those exercises were, the short-story exercise was the most nerve wracking of all. We had to read a short story written with letters that were all reversed, like in a mirror. We received a one-minute instruction in how to decode these, and then the teacher started calling on us to read aloud.

Anxiety rippled through our little group of students. In my head, I prayed silently for the teacher to skip me. By the time it was my turn, I stumbled through the text. Others did better, and I felt bad about myself. Then the teacher asked us what the story was about. I had no clue. I was so focused on just reading the words, I paid no attention to the story.

So what did I learn in this frustrating three-hour process?

- Learning with dyslexia is different than learning without dyslexia. Unless teachers know how to modify their instruction for students with dyslexia, those students will feel frustrated, anxious and may develop a negative self-image.

-Students with dyslexia may need more time to finish an assignment.

-They may need multi-sensory teaching that involves movement, vision and hearing.

-They may need to work in an environment without distractions.

-They will probably feel anxious and intimidated when asked to read aloud to their classmates.

-Hearing things like, “this is easy” or even “you can do it,” may be taken as put-downs rather than encouragement.

-The worst tactic I experienced was the threat of losing recess. Kids need recess and should always get a chance to play, connect with their peers, and move their bodies. Threatening to take that bit of escape away from them does not give them the ability to work faster.

The Orton Academy will offer more of these simulations, and I encourage any teacher or parent to use this opportunity to gain greater empathy and understanding for what students with dyslexia go through.

January 21, 2022

"When two vowels go walking…”

One of many rules taught in school that harm as much as help

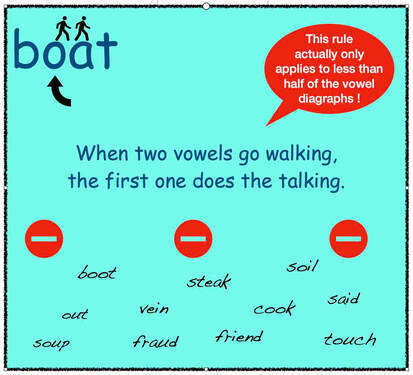

The other day, one of my students tried to read the word chief. We were practicing words with the sound of “ee,” such as meet, seat, and key. She read all the words perfectly—until she got to chief.

For a few moments, she was quiet. Then she said, “That doesn’t make sense. When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.”

She was reciting a rule that is commonly taught in school to help students learn to decode words. But while it’s a catchy rhyme, it confuses and confounds students as often as it helps. That’s because it only applies to about half of the English words with vowel diagraphs.

Sometimes the first vowel “does the talking” by saying its name, as in the words boat and rain. But not in chief and many many other words, including: out, steak, vein, bread, said, friend, fraud, soil, boot, soup, cook and touch.

Would you teach something as a rule if it was only true half the time? You wouldn’t. But unfortunately, many school classrooms still use this and other rules that don’t hold true much of the time. For most learners, this is not a major barrier as their abilities allow them to memorize the (many) exceptions. But for students with reading difficulties, these rules are landmines that deter their progress in reading and undermine their confidence.

With Phono-Graphix, we don’t teach rules. We teach that sounds are represented by one or more sound pictures. For one example, the words cow, out, and drought have different sound pictures for the sound of “ow.” We also teach that a sound picture can represent more than one sound, e.g., the sound picture “ow” can be pronounced “o-e” as in low or “ow” as in cow.

Students learn the sound pictures for each sound, and they learn the important skill of phoneme manipulation—the ability to take sounds in and out of words. For example, the sound picture “ea” represents three different sounds, “e” as in bread, “ay” as in steak, and “ee” as in seat. Students who learn to read with Phono-Graphix are taught to try all three sounds when reading an unfamiliar word containing the sound picture “ea.”

They then figure out which is correct from the context. In the phrase “a loaf of bread,” they would use their oral language skills to ascertain that “ay” and “ee” can’t be correct because no one says “a loaf of braid” or “a loaf of breed.” So “e” must be the correct phoneme for this word.

With Phono-Graphix, there are no rules or exceptions to rules to confuse students: just straightforward simple decoding.

"When two vowels go walking…”

One of many rules taught in school that harm as much as help

The other day, one of my students tried to read the word chief. We were practicing words with the sound of “ee,” such as meet, seat, and key. She read all the words perfectly—until she got to chief.

For a few moments, she was quiet. Then she said, “That doesn’t make sense. When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.”

She was reciting a rule that is commonly taught in school to help students learn to decode words. But while it’s a catchy rhyme, it confuses and confounds students as often as it helps. That’s because it only applies to about half of the English words with vowel diagraphs.

Sometimes the first vowel “does the talking” by saying its name, as in the words boat and rain. But not in chief and many many other words, including: out, steak, vein, bread, said, friend, fraud, soil, boot, soup, cook and touch.

Would you teach something as a rule if it was only true half the time? You wouldn’t. But unfortunately, many school classrooms still use this and other rules that don’t hold true much of the time. For most learners, this is not a major barrier as their abilities allow them to memorize the (many) exceptions. But for students with reading difficulties, these rules are landmines that deter their progress in reading and undermine their confidence.

With Phono-Graphix, we don’t teach rules. We teach that sounds are represented by one or more sound pictures. For one example, the words cow, out, and drought have different sound pictures for the sound of “ow.” We also teach that a sound picture can represent more than one sound, e.g., the sound picture “ow” can be pronounced “o-e” as in low or “ow” as in cow.

Students learn the sound pictures for each sound, and they learn the important skill of phoneme manipulation—the ability to take sounds in and out of words. For example, the sound picture “ea” represents three different sounds, “e” as in bread, “ay” as in steak, and “ee” as in seat. Students who learn to read with Phono-Graphix are taught to try all three sounds when reading an unfamiliar word containing the sound picture “ea.”

They then figure out which is correct from the context. In the phrase “a loaf of bread,” they would use their oral language skills to ascertain that “ay” and “ee” can’t be correct because no one says “a loaf of braid” or “a loaf of breed.” So “e” must be the correct phoneme for this word.

With Phono-Graphix, there are no rules or exceptions to rules to confuse students: just straightforward simple decoding.

|

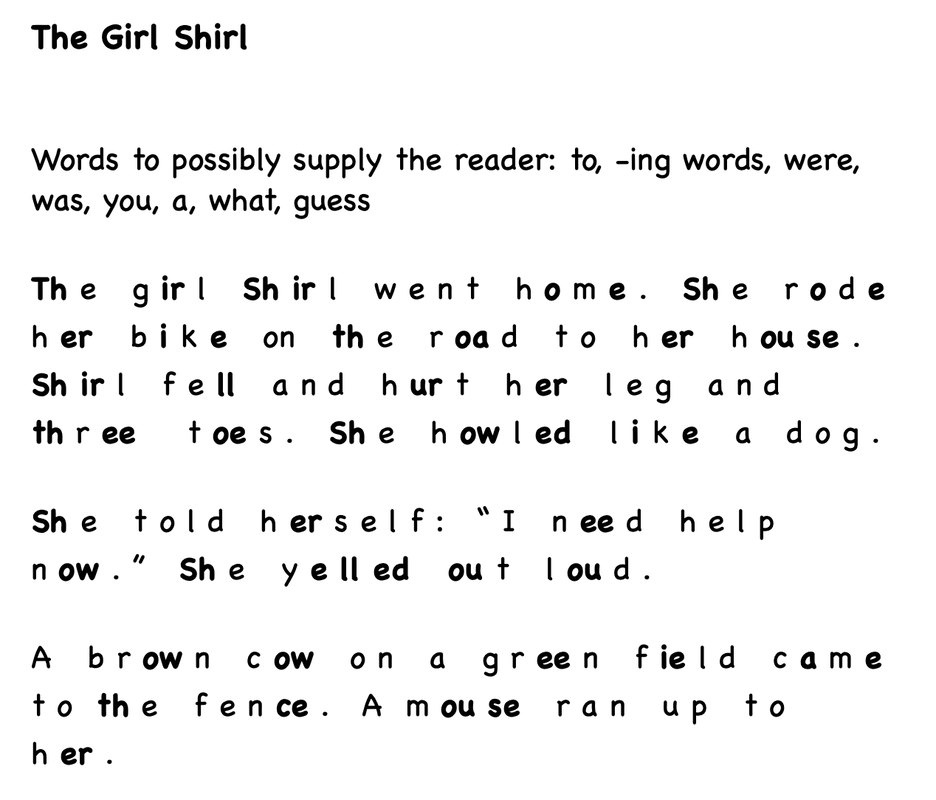

September 4, 2022

The Girl Shirl fell off her bike and hurt her leg. Then she got rescued by her dog and her mom. This silly story won’t win any literary prizes, but it helps my students practice their decoding skills and feel empowered. I wrote this story and others like it so my students can read texts that are just right for their level. A student ready to tackle The Girl Shirl will have learned the most common sounds for all one-letter sound pictures, such as “m,” “l,” and others. They also will have mastered “ck,” “ch,” “sh,” and “th,” and have been introduced to “vowel + e” words like “pine” and “cane” and the sound pictures representing the sounds “oe,” “ow,” “er,” and “ee.” As Phono-Graphix does when providing stories like this to teachers, I have bolded all the sound pictures to help the readers recognize them. Most learners don’t need this kind of structured approach. But for students with reading difficulties such as dyslexia, the explicit decoding approach of Phono-Graphix can enable them to make remarkable progress. In the end, Shirl celebrates her recovery with her mom over cake and a pleasant chat. And for my students, getting to the end of this simple short story is also a victory worth celebrating. |